At the Platform Strategy Research Symposium researchers offer 5 ways to make online platforms more equitable–from accuracy certification to price transparency.

By Paula Klein and Peter Krass

It’s become a common refrain: Platforms are ubiquitous. Whether we’re searching for a job, a news story, groceries or a vacation rental, platforms drive the internet — usually with ease and speed.

Just below the surface, however, complex questions are bubbling up about accuracy, bias, worker displacement, content moderation and regulations. Debates are intensifying as AI algorithms and competition heat up platform markets. Should users determine content accuracy? Is sponsored advertising a good idea? Will data be shared? Are fees transparent enough? Centralize or decentralize?

At the 2024 Platform Strategy Research Symposium held on July 16 at Boston University, global scholars offered cutting-edge data from their latest field experiments and novel ideas to address these pressing issues.

Platform content, moderation and design have changed dramatically in the past few years, and new perspectives, including several explained by researchers affiliated with the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy (IDE), were put forward at the event. Here are highlights of five of the day’s presentations.

1. Re-imagining Jobs Since GenAI

A key question these days is which jobs will be displaced by AI. A group of researchers represented by Ozge Demirci, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Business School, studied the impact of Generative AI on online freelancing platforms. Demirci presented findings of their paper, Who is AI Replacing?, which examined more than1.7 million online job posts. The researchers found that after the launch of ChatGPT, writing and coding job posts dropped by 21%. Similarly, after the launch of GenAI tools for image creation such as Midjourney, job posts related to image creation declined by 17%.

During the comments portion of the presentation, Emma Wiles, assistant professor of information systems at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business and a digital fellow at the IDE, suggested that job “substitution” rather than job replacement could be occurring. That is, employers may be hiring different types of skills as ChatGPT emerges. Wiles also suggested that freelancers might be re-imagining jobs and applying for different kinds of jobs or supplementing their skill sets in light of AI.

2. Giving Applicants a Boost

Freelancers were also studied by another group of researchers represented at the event. This research team wanted to know what happens when job-seekers pay platforms to have their personal profiles prominently displayed to potential employers. Would employers view these ads as credible displays of interest or as acts of desperation?

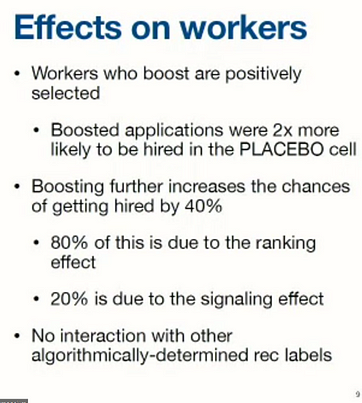

Answers were provided by Prasanna Parasurama, assistant professor at Emory’s Goizueta Business School. Parasurama co-authored a paper on the effects of sponsored advertising with MIT researchers Apostolos Filippas and John Horton.

Their study asks: What is the impact on employers and job-seekers of “boosting” applications on online labor markets? The practice is already happening, according to their paper, Decomposing the Signaling and Ranking Effects of Sponsored Advertising: Experimental Evidence from an Online Labor Market.

Several online platforms let sellers pay to have their listings highlighted. “Sponsored advertising” was pioneered by internet search engines and has since become a core feature in online platforms. For example, Amazon reported $47 billion in 2023 advertising revenue, according to the paper.

Paying for job applicants is fairly new, however. The study examined advertising where freelance applicants could bid to boost their applications with prospective employers.

The experiment looked at 3.6 million job applications from some 500,000 workers over a two-month period in 2021. About a quarter of those workers highlighted their application. The results were both dramatic and surprising: Boosting increases a person’s chances of being hired by about 40%. And employers generally like seeing the boosted ads; they saw it as a sign of high interest in the job. Parasurama said nearly 80% of the increase resulted from the ranking effect — boosted applications ranking higher — and just over 20% was due to the disclosure that the application is boosted.

3. Self-Certifying the Truth

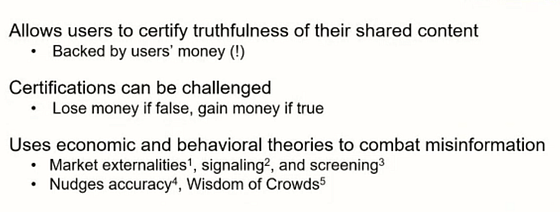

A provocative idea to address the lack of accuracy on social media platforms was put forth by Aaron Nichols, a doctoral candidate at Boston University. Citing data from the World Economic Forum that misinformation is the biggest global problem of 2024, Nichols and fellow researchers sought an out-of-the-box solution to certify accuracy without limiting free speech. The team, including MIT IDE researchers David Rand and Marshall Van Alstyne, introduced and evaluated a novel, decentralized platform-level intervention known as self-certification.

According to their paper, Certifiably True: The Impact of Self-Certification on Misinformation, self-certification “allows individuals to voluntarily attest to the truthfulness of the information they share.” The mechanism would present what the researchers describe as a “scalable and user-driven solution to combat misinformation.”

Nichols described the current social media environment as one where “likes” amplify information that is the most sensational — not the most accurate — and where deterrents have little effect. Further, he argued, decentralized, platform-level interventions don’t require a third-party arbiter empowering users toward truthfulness. The approach provides small financial incentives for sharing the truth, and penalties for those sharing misinformation. The goal: enhance the visibility and trustworthiness of accurate information.

Experimental results with roughly 4,000 social media users show large increases in discernment — people share much less false information, but also share much more true information. Most other studies that succeed at reducing falsity don’t succeed at boosting truth. In this new approach, total engagement actually rises, according to the researchers.

The study is still in the early stages. As Nichols explained, further testing will determine whether self-certification offers a viable intervention to misinformation.

Self-certification:

4. The Value of Price Transparency

Why do platforms–from vacation rental sites to ticket sellers — persist in hiding the buyer’s true costs? That topic was studied by MIT researchers Jose Lopez and Geoffrey Parker, along with Edward Anderson of the University of Texas, Austin.

Lopez presented their study, The Hidden Cost of Hidden Fees: A Dynamic Analysis of Price Obfuscation, which examines the effects of “shrouding hidden fees” on consumer behavior and platform firm performance.

While economic models show that hidden fees can be profitable in the short term, more recent work in behavioral operations management argues that “these tactics can be harmful, not just to consumers but to the firms themselves,” the paper states. The researchers also analyzed the performance dynamics of shrouding versus transparent platforms, and they recommend that firms take a long-term view perspective. The paper asserts that while “managers may be tempted to abandon transparency efforts in favor of short-term financial benefits…such a strategy can undermine trust and reputation in the long term, hindering the development of enduring consumer loyalty.”

5. Decentralized Data Sharing

Rethinking competitive advantage was also the theme of a presentation by Georgios Petropoulos, a researcher at the IDE and a Digital Fellow at Stanford University. As he explained, some platforms have created super-structures with unique access to information that can lead to data bottlenecks, market asymmetries and failures. Data concentration of this type provides a lot of value to the platform owner, but very little value to anyone else.

Petropoulos said a decentralized, data-value redistribution mechanism is needed. He cited the European Union’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) as a good first step, although its terms are overly vague. Petropoulos and his colleagues — including IDE visiting scholar Geoffrey Parker and IDE Digital Fellow Marshall Van Alstyne — propose a new model that would financially incentivize very large platforms to share non-personal market data with their competitors, helping smaller organizations improve their value proposition.

Their paper, Platform Competition and Information Sharing, calls for mandatory information sharing by big platforms to their competitors to benefit both large and incumbent firms.